Good Intentions

- Sean Smith

- Jul 30, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 31, 2025

The setting for my novel Transformation Summer (the reason why this website came into existence in the first place) is an all-ages summer camp, Toward Transformation, where the attendees run everything. There's no staff, no invited experts to offer the benefits of their experience and wisdom. At "Transformation" (as it's called for short), if you have a skill or insight that you can share -- whether it's in gardening, yoga, cooking, home finances, American history, music or interpersonal relationships -- you sign up to lead a class or workshop. Any one of the people who come listen to you in the morning might be leading the class or workshop that you go to in the afternoon.

In constructing Toward Transformation, I partly drew on memories and experiences from the youth programs run by the Quaker meeting I attended during my pre-teen and teenage years. The programs took place in a small conference center next to the meeting house; the building included dormitories, a kitchen and a large multi-purpose room. Typically, everyone -- upwards of two-dozen or so kids -- would arrive on a Friday evening and stay until Sunday afternoon. Each session would have a focus of some kind, like Conflict and Peace, or Interpersonal Relationships, and the youth program directors organized and led discussions and activities centered around that theme. But you also had free time to go for walks, play board games, listen to music, or best of all, just to sit and talk with one another.

At the end of these sessions, I felt like I had been someplace very special -- a place that had its own language and customs -- and part of what made it so was that I had shared the experience with friends.

While I was in the late stages of writing Transformation Summer, I explained the concept behind Toward Transformation to a friend, who nodded and said, "Oh, so it's an intentional community."

I had heard of intentional communities, but I associated them with, say, housing co-ops, or kibbutzim, or communes -- places organized around a long-term time commitment, as opposed to Transformation's two-week duration, and more importantly, based on some guiding social, economic or other principles. The more I thought about it, though, the more I felt that perhaps "intentional community" was an appropriate description for Transformation, and some other places, too, like the Quaker youth programs I so enjoyed.

Earlier this summer, I attended what I consider to be another example of a "short-term" intentional community: Pinewoods, a camp located in Plymouth, Mass., that for the better part of a century has offered various programs in American, English, Scottish and other kinds of folk music and dance from May to October. There are families who have gone to Pinewoods literally for generations, so it's a place steeped in history and tradition.

Pinewoods is situated in a forest of birch and pine nestled between two large ponds. Like Toward Transformation, it's rustic but not primitive: The cabins, camp houses and other structures have electricity, and there's running water, toilets and showers. So you don't have to be a hard-core lover of the outdoors to enjoy yourself.

The daily schedule is full of various workshops and activities (depending on the focus of the program session) and the evening is taken up by a main event -- typically a dance or concert, if not both. Nothing says that you have to participate in any of these; the only requirement in attending Pinewoods, per se, is that each camper is assigned a small job, either a daily or a one-time task. If you want, you could just spend the day hiking around the woods, sitting and reading (the camp has its own little library), playing cards or napping.

But Pinewoods isn't a resort. There's no bar or café to hang out in, where you can order drinks and get a bite to eat (though there are parties in the late afternoon or at the end of the evening). More importantly, not participating in the camp program is like going to the world's finest art museum and then spending time in the gift shop instead of browsing the exhibits.

It's not dissimilar at Transformation: As we learn from Marcus, one of its founders, people don't have to take part in any of the workshops -- and in fact some families do take a day or so to go do their own thing -- but if you've signed up to come, doesn't it make sense to see what you can learn? You're not in this alone, after all, but amidst people who place value on the camp and what it does; a community, if you will.

Yet the formal program at Pinewoods, Toward Transformation, or most any other similar short-term intentional community is only part of the experience. The informal, more personalized activities that occur at the margins are at least as important. The group of kids that our Transformation Summer protagonist Seth hangs out with have their own itinerary, some of which would surely not be condoned by adults: ritual fully-clothed immersion into the lake, illicit skinny dipping, indulging in a little wine and pot, or just playing frisbee. All are part of the bond they've formed over the years at Transformation.

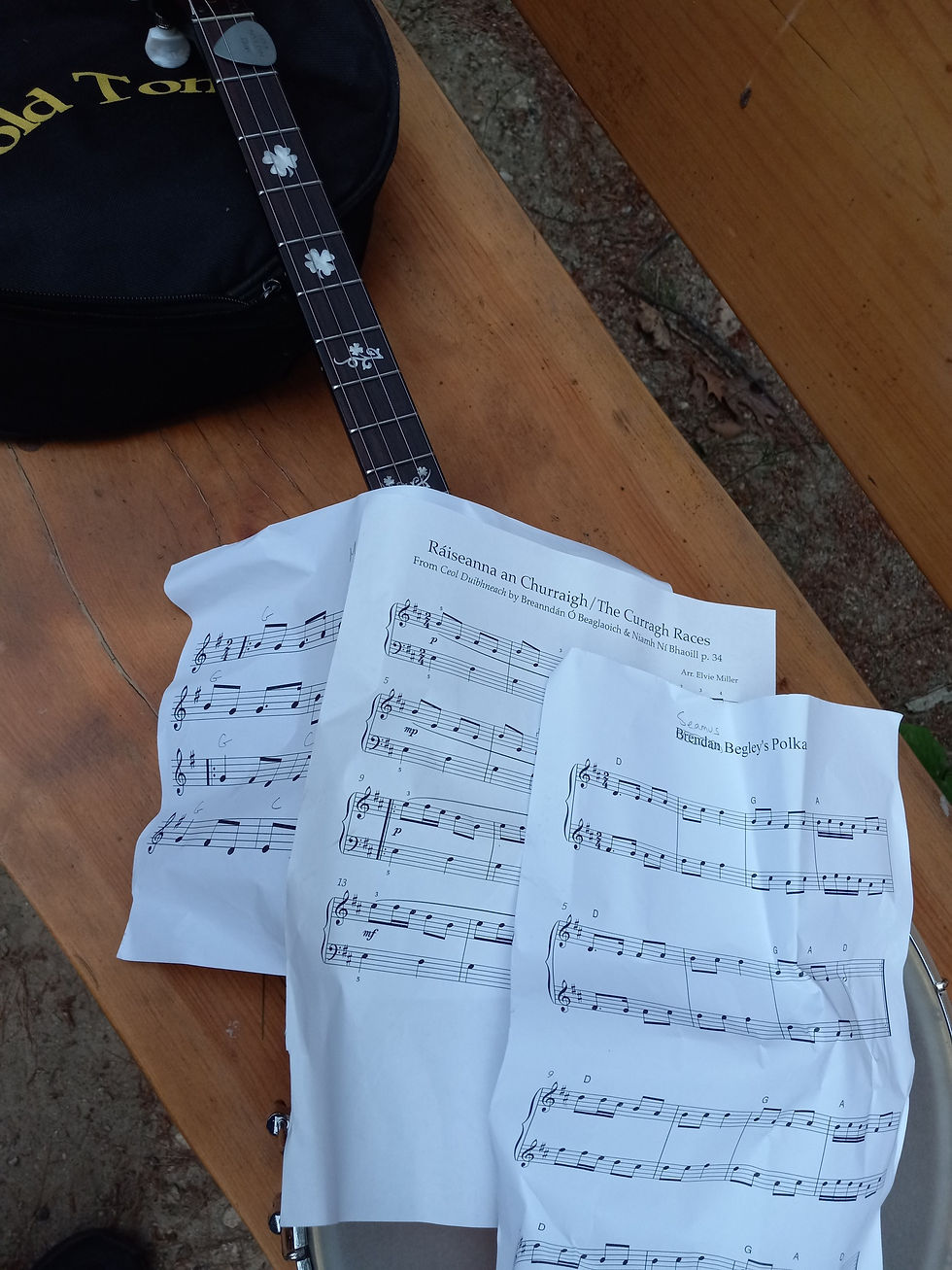

Many of the people who go to Pinewoods see one another elsewhere during the year, but being at the camp together offers opportunities to enrich or deepen friendships: hiking and swimming together, having a little jam session or sing-around, or simply hanging out at one's cabin. I know a couple of people who make a point of playing ping-pong every time they're at the same Pinewoods session -- a game observed by other friends and acquaintances, with plenty of commentary.

However much you might get out of the formal program, somehow it's not quite the same if you don't have those little rituals or rites you've long enjoyed.

There is one important difference between the paradigmatic intentional communities I mentioned earlier, and the short-duration, recurring ones like Pinewoods or Toward Transformation. With the latter kind, I think, you have more of a sense that you are stepping outside of, or withdrawing from, the wider world. You are away from your usual surroundings, your usual routine, and you have to adapt (more or less) to the physical and temporal characteristics of this other ecosystem.

And then, once the camp or program is over, you have to go the other way and re-enter what we invariably call "the real world." I'm sure not alone when I say I've found that to be a tough transition: Why must I go back to my workaday life of wake up/shower/ breakfast/commute-to-office/job/commute-home/dinner etc.? Is there some aspect of this place, this experience I can hold onto?

At the end of this most recent Pinewoods sojourn, after I'd loaded up my stuff and started up the car, and noticed that there was quite a collection of needles from adjacent pine trees dotting the windshield. I was about to turn on the wipers when I thought better of it. They weren't impeding my visibility. Let them stay on a little longer.

I drove slowly along the access road from the camp, pulled out onto a town road and slowly picked up speed. One by one, the pine needles fell off, and within about five minutes my windshield was all clear. My Pinewoods weekend was truly over.

Comments